Microlight to Portugal | The Independent

The Independent on Sunday | 11 July 1999

On a wing and a prayer

There are many ways of getting to Portugal, but for Laura Ivill, only the microlight way would do

[Read the online version The Independent newspaper]

I sat behind, with my legs wrapped around Tim, my pilot and boyfriend. Either side were two full spare fuel cans, strapped on to the pod, just below where my arms rested. Tim was running through the power checks. I heard the tiny single engine roar from behind. I heard him muttering out loud: "Controls, harness and helmet secure," (I said yes into my intercom, saw him nod), "instruments, fuel, wind, all clear on the runway, power."

We surged forward, bouncing down the top corner of the field. I heard Tim say "Up, up, now" under his breath and then, always a miracle, she hopped up and lumbered rather than shot skyward.

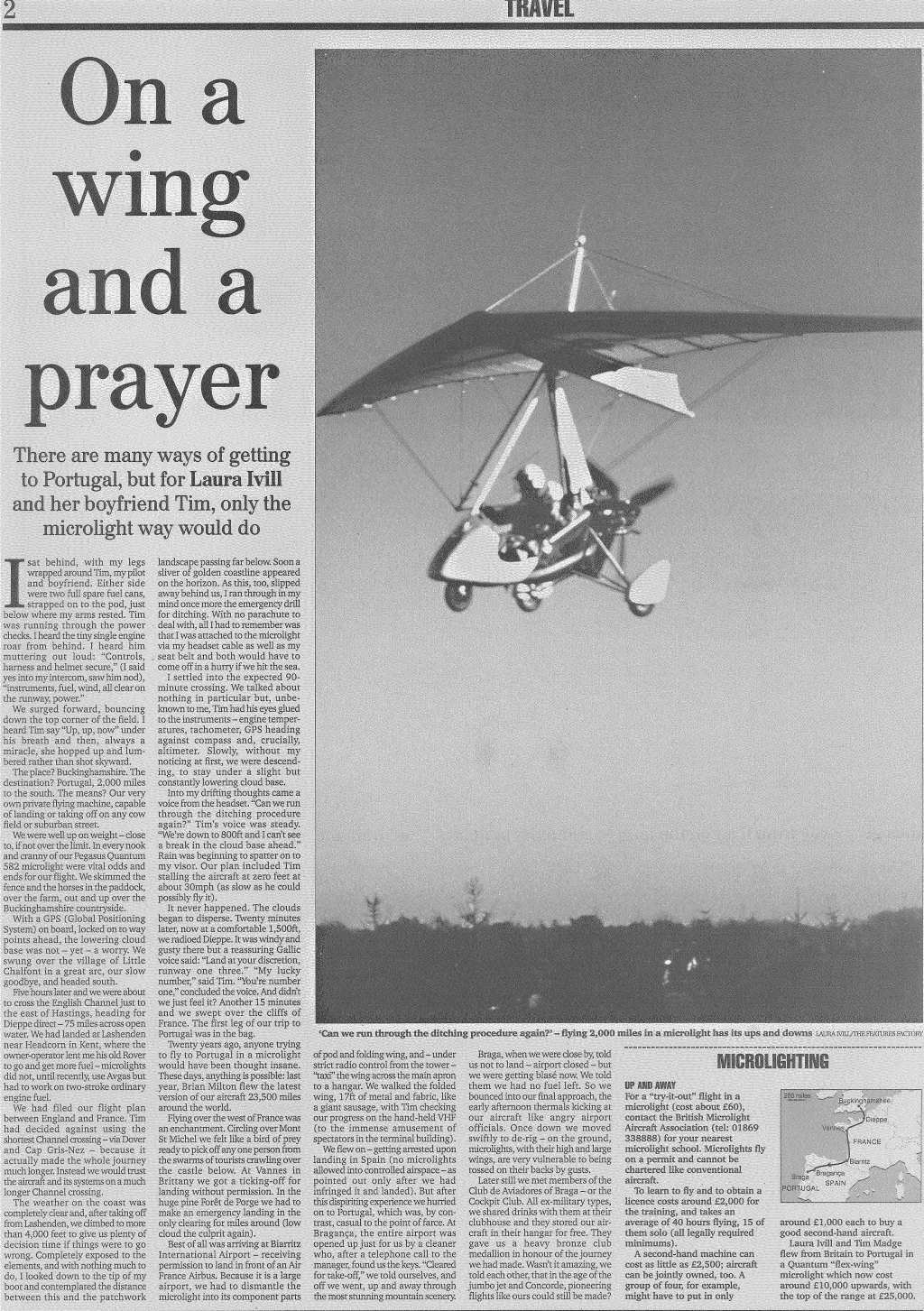

The place? Buckinghamshire. The destination? Portugal, 2,000 miles to the south. The means? Our very own private flying machine, capable of landing or taking off on any cow field or suburban street.

We were well up on weight - close to, if not over the limit. In every nook and cranny of our Pegasus Quantum 582 microlight were vital odds and ends for our flight. We skimmed the fence and the horses in the paddock, over the farm, out and up over the Buckinghamshire countryside.

With a GPS (Global Positioning System) on board, locked on to way points ahead, the lowering cloud base was not - yet - a worry. We swung over the village of Little Chalfont in a great arc, our slow goodbye, and headed south.

Five hours later and we were about to cross the English Channel just to the east of Hastings, heading for Dieppe direct - 75 miles across open water. We had landed at Lashenden near Headcorn in Kent, where the owner- operator lent me his old Rover to go and get more fuel - microlights did not, until recently, use Avgas but had to work on two-stroke ordinary engine fuel.

We had filed our flight plan between England and France. Tim had decided against using the shortest Channel crossing - via Dover and Cap Gris- Nez - because it actually made the whole journey much longer. Instead we would trust the aircraft and its systems on a much longer Channel crossing.

The weather on the coast was completely clear and, after taking off from Lashenden, we climbed to more than 4,000 feet to give us plenty of decision time if things were to go wrong. Completely exposed to the elements, and with nothing much to do, I looked down to the tip of my boot and contemplated the distance between this and the patchwork landscape passing far below. Soon a sliver of golden coastline appeared on the horizon. As this, too, slipped away behind us, I ran through in my mind once more the emergency drill for ditching. With no parachute to deal with, all I had to remember was that I was attached to the microlight via my headset cable as well as my seat belt and both would have to come off in a hurry if we hit the sea.

I settled into the expected 90- minute crossing. We talked about nothing in particular but, unbeknown to me, Tim had his eyes glued to the instruments - engine temperatures, tachometer, GPS heading against compass and, crucially, altimeter. Slowly, without my noticing at first, we were descending, to stay under a slight but constantly lowering cloud base.

Into my drifting thoughts came a voice from the headset. "Can we run through the ditching procedure again?" Tim's voice was steady. "We're down to 800ft and I can't see a break in the cloud base ahead." Rain was beginning to spatter on to my visor. Our plan included Tim stalling the aircraft at zero feet at about 30mph (as slow as he could possibly fly it).

It never happened. The clouds began to disperse. Twenty minutes later, now at a comfortable 1,500ft, we radioed Dieppe. It was windy and gusty there but a reassuring Gallic voice said: "Land at your discretion, runway one three.'' "My lucky number," said Tim. "You're number one," concluded the voice. And didn't we just feel it? Another 15 minutes and we swept over the cliffs of France. The first leg of our trip to Portugal was in the bag.

Twenty years ago, anyone trying to fly to Portugal in a microlight would have been thought insane. These days, anything is possible: last year, Brian Milton flew the latest version of our aircraft 23,500 miles around the world.

Flying over the west of France was an enchantment. Circling over Mont St Michel we felt like a bird of prey ready to pick off any one person from the swarms of tourists crawling over the castle below. At Vannes in Brittany we got a ticking-off for landing without permission. In the huge pine Foret de Porge we had to make an emergency landing in the only clearing for miles around (low cloud the culprit again).

Best of all was arriving at Biarritz International Airport - receiving permission to land in front of an Air France Airbus. Because it is a large airport, we had to dismantle the microlight into its component parts of pod and folding wing, and - under strict radio control from the tower - "taxi" the wing across the main apron to a hangar. We walked the folded wing, 17ft of metal and fabric, like a giant sausage, with Tim checking our progress on the hand-held VHF (to the immense amusement of spectators in the terminal building).

We flew on - getting arrested upon landing in Spain (no microlights allowed into controlled airspace - as pointed out only after we had infringed it and landed). But after this dispiriting experience we hurried on to Portugal, which was, by contrast, casual to the point of farce. At Braganca, the entire airport was opened up just for us by a cleaner who, after a telephone call to the manager, found us the keys. "Cleared for take-off," we told ourselves, and off we went, up and away through the most stunning mountain scenery.

Braga, when we were close by, told us not to land - airport closed - but we were getting blase now. We told them we had no fuel left. So we bounced into our final approach, the early afternoon thermals kicking at our aircraft like angry airport officials. Once down we moved swiftly to de-rig - on the ground, microlights, with their high and large wings, are very vulnerable to being tossed on their backs by gusts.

Later still we met members of the Club de Aviadores of Braga - or the Cockpit Club. All ex-military types, we shared drinks with them at their clubhouse and they stored our aircraft in their hangar for free. They gave us a heavy bronze club medallion in honour of the journey we had made. Wasn't it amazing, we told each other, that in the age of the jumbo jet and Concorde, pioneering flights like ours could still be made?

MICROLIGHTING

UP AND AWAY

For a "try-it-out" flight in a microlight (cost about pounds 60), contact the British Microlight Aircraft Association(tel: 01869 338888) for your nearest microlight school. Microlights fly on a permit and cannot be chartered like conventional aircraft.

To learn to fly and to obtain a licence costs around pounds 2,000 for the training, and takes an average of 40 hours flying, 15 of them solo (all legally required minimums).

A second-hand machine can cost as little as pounds 2,500; aircraft can be jointly owned, too. A group of four, for example, might have to put in only around pounds 1,000 each to buy a good second-hand aircraft.

Laura Ivill and Tim Madge flew from Britain to Portugal in a Quantum "flex-wing" microlight which now cost around £10,000 upwards, with the top of the range at £25,000.